When I started watching cycling, I had no idea why cyclists keep going into a breakaway if it’s always caught before the finish. But the more I watched, the more I understood. I also realized that successful breakaways are more common than I first thought.

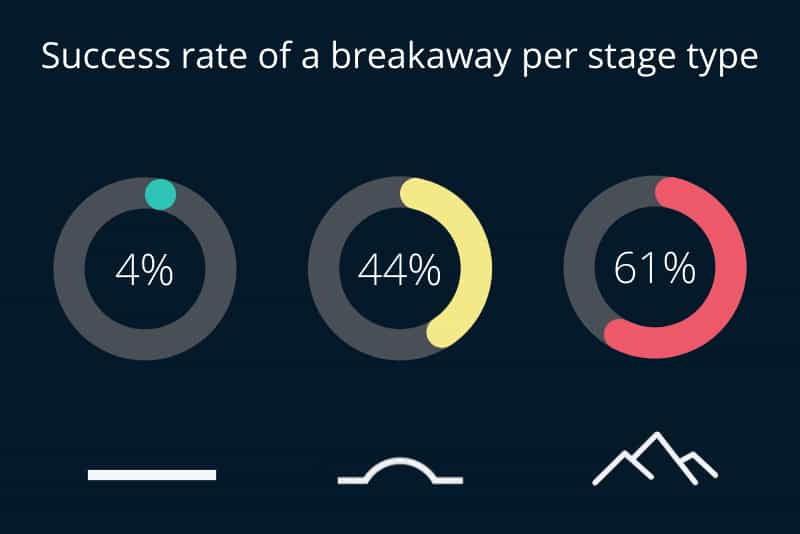

On average, 44% of breakaways end in a win. The most successful breakaways are on mountain stages, with a 61% win rate, while the least successful are on flat stages, with only 4% ending in a win. On hilly stages, the success rate is precisely the same as the average, at 44%.

Many factors contribute to the success of the breakaway. Of course, the type of stage is an important one, but by no means the only one. Below, I will present each of them and analyze their importance.

Are breakaways really doomed to failure?

Most people assume breakaways don’t have any chance of winning. Even if you check some websites and forums, you’ll get the idea that going in a breakaway is a waste of energy, as winning is impossible.

That’s not true!

Firstly, there are also other reasons to join a breakaway besides victory. I actually wrote an article about why cyclists join the breakaway that will help you get the broader picture of the breakaway as a whole.

Secondly, if you do the proper analysis, you see that breakaways are much more successful than one might think.

Breakaways have been part of cycling since the beginning.

Luckily you don’t have to do the analysis yourself, as I did it for you. I analyzed 110 stages across six Grand Tours in 2020 and 2021.

The results I got surprised me!

Exactly 48 stages were won by a rider from the early breakaway. That’s 44% of all stages. For me, that’s an insane number that proves that joining a breakaway makes sense.

Most riders who join the breakaway don’t have the chance to win from the peloton, so breakaway offers them a unique opportunity to get to the victory they so desperately want. And with a 44% breakaway win rate, their chances are not so slim.

Before I go on with a more detailed analysis, let me mention that the data are based on stage races. The way of racing in one-day races is completely different, making the role of breakaways much smaller.

How does the type of stage affect the success of breakaway?

As mentioned at the beginning, the type of stage plays a big role in the success of a breakaway. Perhaps even the biggest of all factors.

There are three types of stages – flat, hilly, and mountain.

For most stages, you can predict if a breakaway will win it. Flat stages are the hardest to win, while hilly and mountain stages offer more opportunity. Cyclists know that, so they pick their stages very carefully.

Flat stages

Flat stages are reserved for sprinters. They come to the race only for stage wins, as they cannot compete for high positions in the overall standings. Flat stages offer them the easiest way to get the win, so they’ll make sure the breakaway doesn’t take it away from them.

Normally, there are a few sprinters at the race, so more teams are willing to share the duty of chasing the breakaway. The more teams involved, the lower the chances for a breakaway.

There were 19 flat stages in my analysis, and only once was the breakaway successful. This amounts to only 4%, which explains why cyclists are reluctant to participate in breakaways on flat stages.

Hilly stages

Hilly stages are the trickiest to predict. The ‘hilly’ designation covers a wide range of stages – from those with only a few bumps along the way to those that could almost be classified as a mountain.

Easier hilly stages are often won by sprinters, so breakaway suffers a similar fate to the flat stages. The harder the stage gets, the more chances are for the breakaway to succeed. But the stage must not be too challenging, as overall favorites might catch them on the climbs.

Riders in a breakaway don’t want a stage to finish on top of the climb. They would rather see that the finish line is in the valley, with the last mountain top a few miles away from the finish.

The riders in a breakaway are much more tired in the last miles than the chasers. So any climbs late in the stage lowers their chances, as some riders from the chase might sense they can bridge to the breakaway and then attack from there. With much fresher legs, riders from the peloton tend to be successful.

I analyzed 42 hilly stages, and a breakaway won 18. That amounts to 44%. Most of the hilly stages that weren’t won by breakaway had either super easy or super hard final.

Mountain stages

Breakaways are the most successful on mountain stages. The toughest stages are still reserved for general classification (GC) contenders, but everything else is up for grabs.

GC guys don’t waste energy, they spread it very deliberately throughout the race. The same goes for the energy of the rest of the team. There are 7-10 mountain stages on Grand Tour, so if one team had to do the chasing on all of them, its cyclist would burn out before the decisive stages.

On mountain stages, it’s common for a breakaway to have ten or more minutes advantage. As long as nobody is a threat to the general classification, the favorites don’t care about the breakaway.

On less challenging mountain stages, teams of favorites let the breakaway go. That way, they can save energy, as their only job is only to control the time gap, so there wouldn’t be any major shakeups in the general classifications. The amount of energy they need to control the breakaway is much less than when they need to chase.

I have included 46 mountain stages in my analysis. Twenty-eight of them were won by a breakaway, a staggering 61%.

How the number of riders in the breakaway affects the success

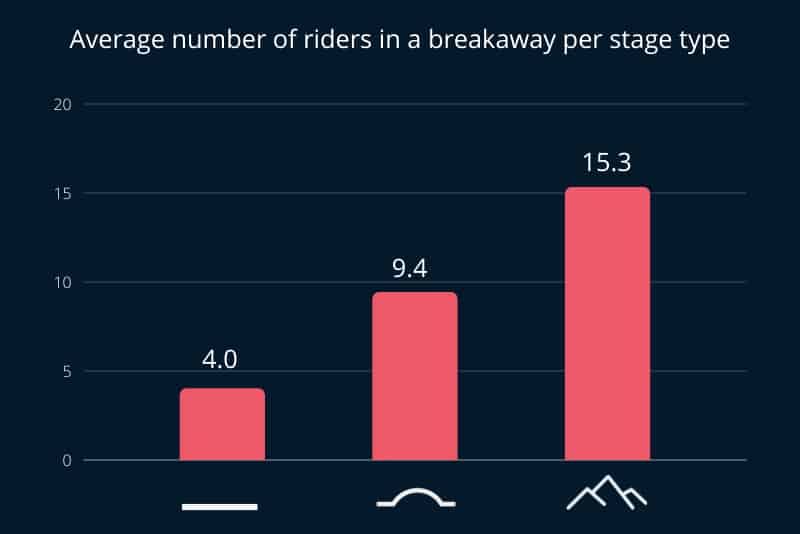

One-man breakaway will almost never win, while a 30-man breakaway will win most of the time.

The number of riders in a breakaway is a crucial factor for its success. The more riders there are, the less work each has to do.

In big breakaways, riders can better distribute their energy throughout the whole stage, so the speed remains high to the finish. Therefore peloton has a hard time catching them and won’t even bother setting up a proper chase in most cases.

Flat stages attract the fewest cyclists to the breakaway. With only 4% chances of success, you can understand that cyclists are not so keen on suffering the whole day to be then caught a few miles before the finish line.

On average, only four cyclists join the breakaway on flat stages. These are usually riders from smaller teams who have to show their sponsors’ names to the cameras. Those selected for breakaways on flat stages often see it as a punishment rather than a reward.

Here we have a kind of vicious circle. Due to the low success of breakaways on flat stages, fewer cyclists decide to join. But with fewer riders, the chances of winning are lower. So if more riders chose to break away, they would also have a better chance of winning the flat stages.

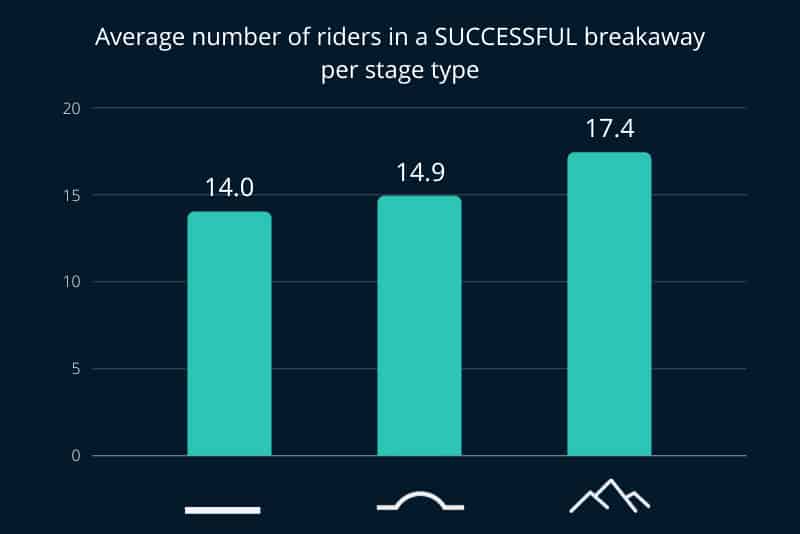

On average, 15.4 cyclists take part in a successful breakaway. The highest number of participants is on mountain stages (17.4), while the lowest number is on flat stages (14.0). On hilly stages, an average of 14.9 cyclists take part in a successful breakaway.

As you can see, on average, successful breakaways require more cyclists than a ‘regular’ breakaway. This is especially true for the flatter stages, where it is easier for the peloton to control and catch breakaways.

The smallest difference between the number of riders in the ‘regular’ breakaway and the successful breakaway is on mountain stages.

This is because a larger number of cyclists get involved in the breakaway on mountain stages anyway. I also mentioned that the peloton is less keen on chasing breakaways on mountain stages, so the number of riders in the breakaway doesn’t play as big a role in success.

The number of riders in a breakaway is the most important on hilly stages. The peloton is much keener on chasing there, so having many riders in a breakaway will make them think twice if chasing is really worth it. And even if they decide to chase, it’s not guaranteed they will be successful.

The number of successful breakaways varies from year to year

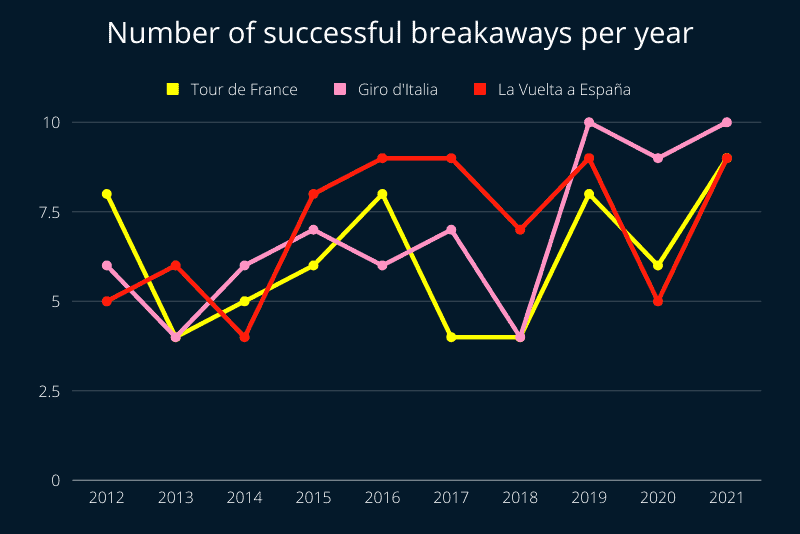

It’s impossible to say how many breakaways will be successful in any given race. The number varies greatly from year to year and even from race to race.

The success rate depends on the course of the race. If there are large time gaps at the beginning, breakaways are much more likely to succeed than if the time gaps are small.

So how do we get big gaps early on?

In most cases, this depends on the route. There will be significant gaps if there are some hilly or even mountain stages in the first few days. Some riders will even deliberately fall behind and lose time, giving them more chances to be allowed in a breakaway in the following stages.

The other factor is the ratio between easier (flatter) stages and harder (mountain) stages. The more of the latter, the more successful breakaways there will be.

Each race has different characteristics, determined by geography, tradition, and the organizer’s preferences. The combination of these determines the chances of successful breakaways.

La Vuelta a España is traditionally a very hilly race, so we get to see many successful breakaways. On the other hand, the Tour de France has a more even stage ratio, so there will be fewer breakaways.

Tour de France and Giro d’Italia also rarely have a mountain stage in the first few days, while that’s not so unusual at La Vuelta a España. Therefore, breakaways are more successful at La Vuelta.

However, we will see a few successful breakaways every year on every race, whatever the route. After all, it’s up to the cyclists to turn opportunity into victory.